How does the individual researcher influence data collection? Report on a methodological experiment investigating the Linguistic Landscape of Istanbul

Authors: Laurentia Schreiber (Universität Bamberg) & Ruth Bartholomä (Orient-Institut Istanbul)

15 August 2024

Introduction: How did it all start?

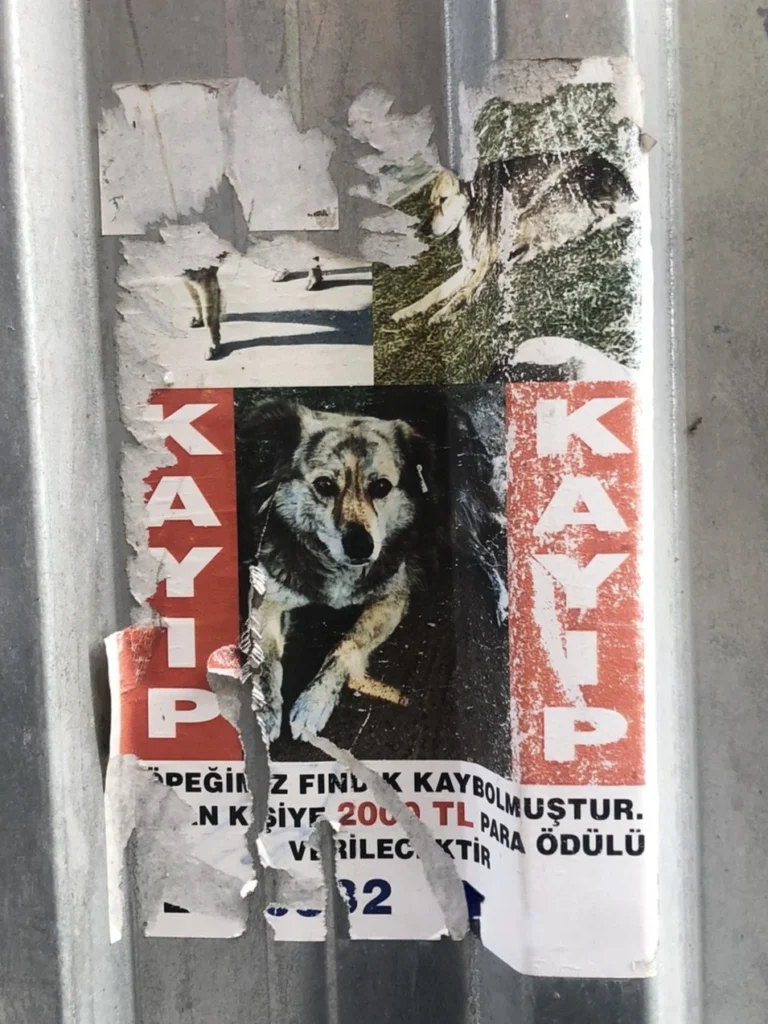

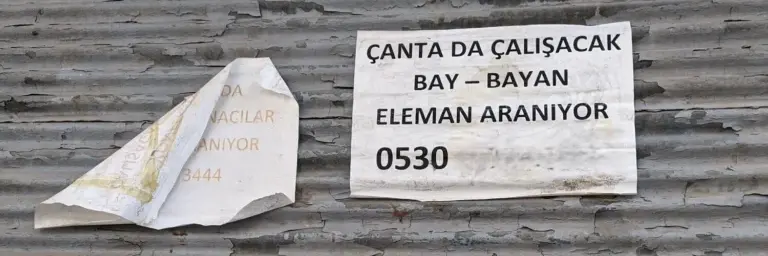

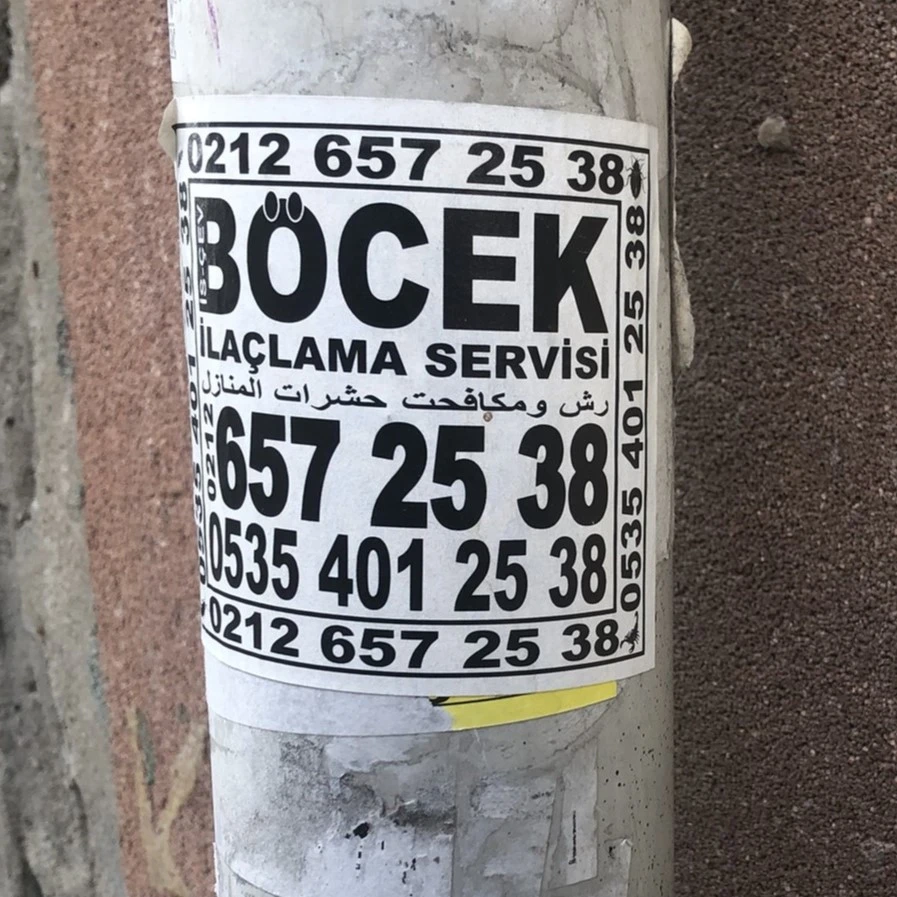

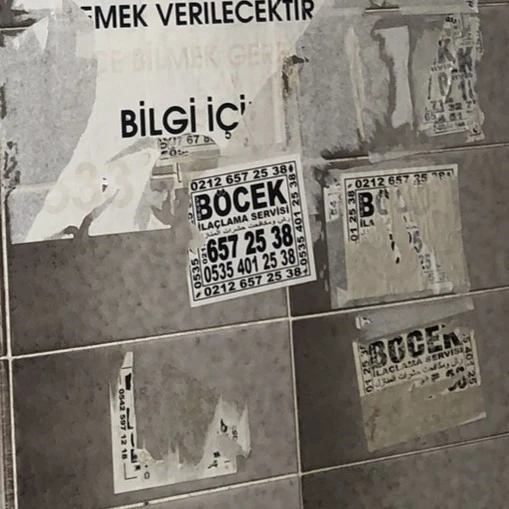

Between 30 November and 2 December 2023, the Orient-Institut Istanbul, together with the Municipality of Istanbul (İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi) and the University of Potsdam, organized a workshop on the ‘Linguistic Landscape of Istanbul: Possibilities and Prospects’. Within sociolinguistics, Linguistic Landscape (LL) research is an approach developed since the 1990s that aims to make urban multilingualism visible by researching the appearance of (mostly written) language in the publicly visible landscape, that is often enough a ‘cityscape’ (see, e.g., Laundry & Bourhis’ 1997 seminal work on the new approach). The object of research are any written manifestations of language(s) such as advertisement walls, shop signs, street boards, and other signage, whose analysis is assumed not only to depict the variety of languages present but also hierarchies and power relations between the languages, which are essentially indicators of power relations between groups of speakers. Linguistic Landscape data is usually collected by means of photographic documentation of written signs (see Fig. 1–3 for examples from Istanbul).

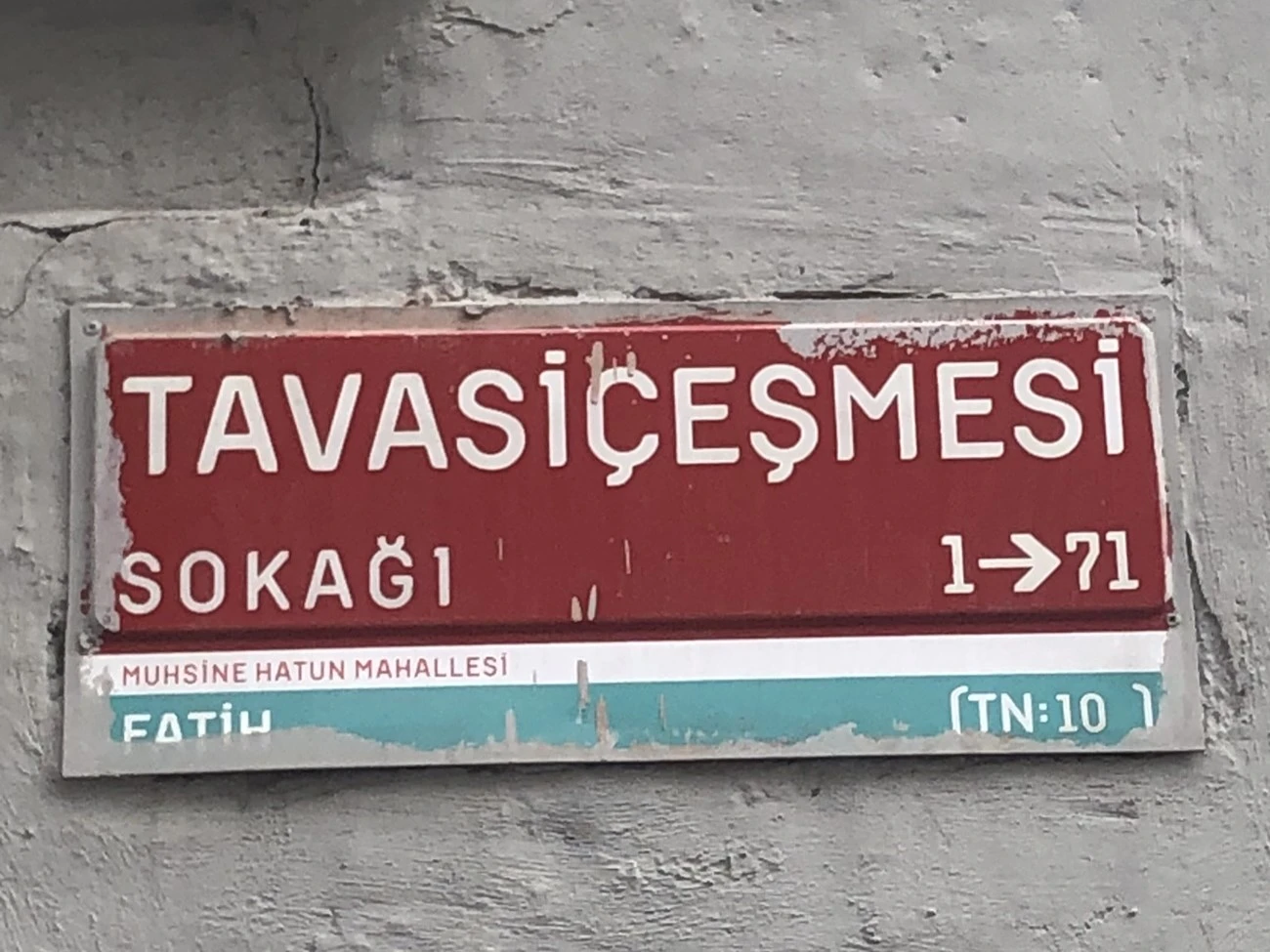

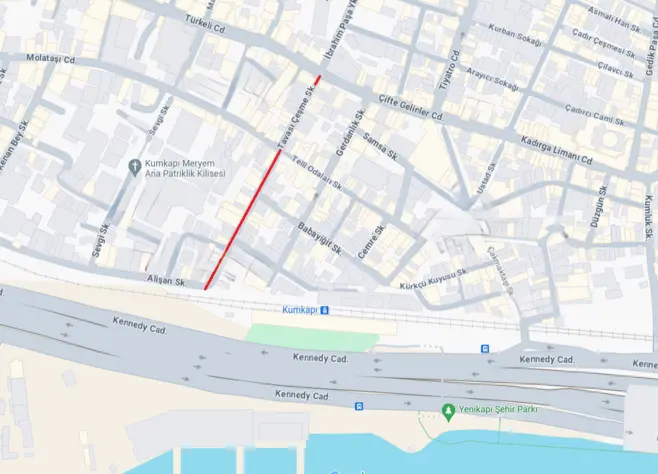

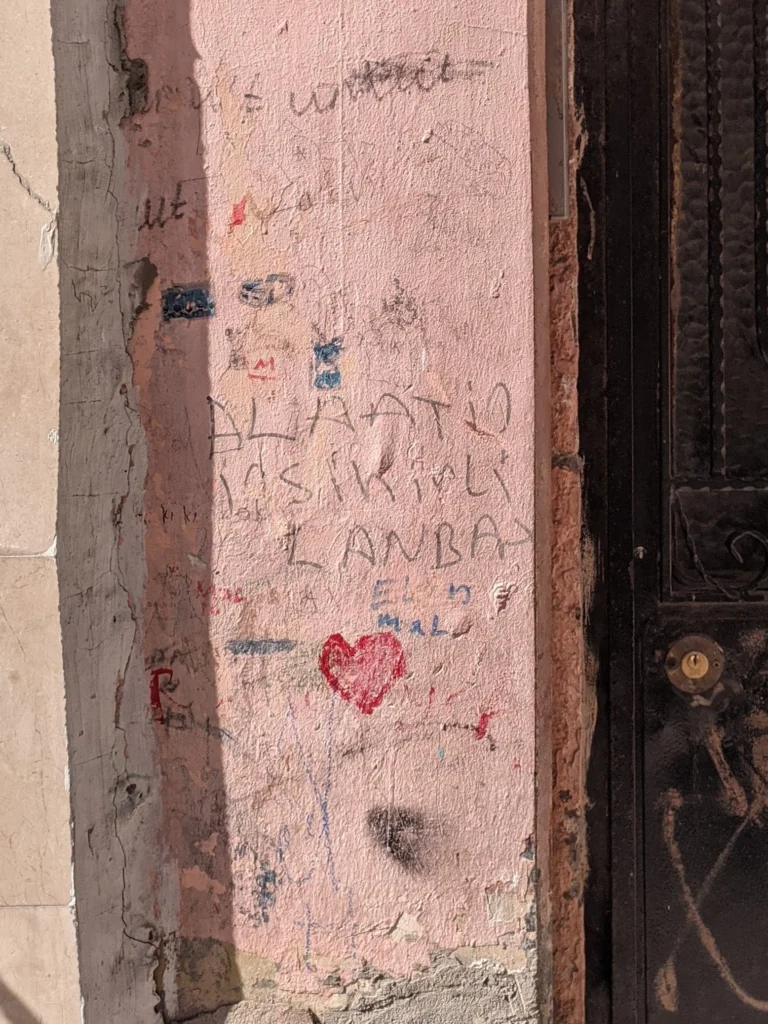

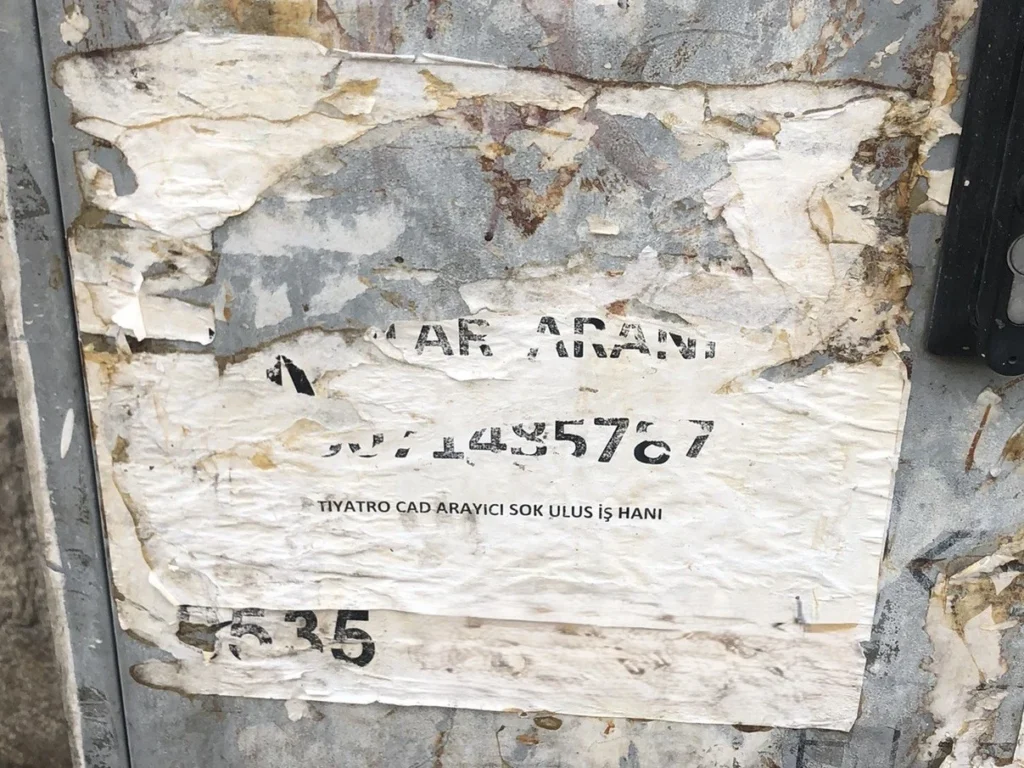

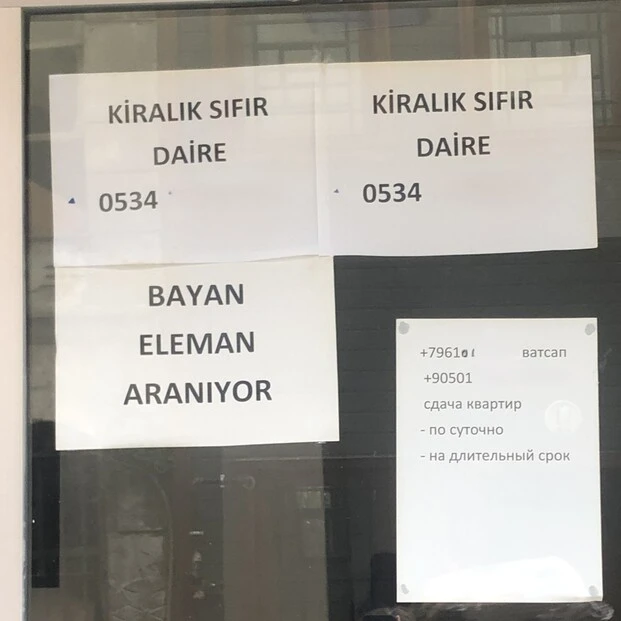

Fig. 1–3: Examples for the Linguistic Landscape of Istanbul, Fatih district, Kumkapı/Muhsine Hatun neighbourhood. All photos in this blogpost were taken by Laurentia Schreiber and Ruth Bartholomä. Private telephone numbers have been removed for reasons of data protection.

The workshop on the ‘Linguistic Landscape of Istanbul’ had been originally planned for February 2023 but was postponed due to the disastrous earthquake that hit Turkey at the beginning of that month. The authors of this article, however, met anyway to exchange on their previous research on the Linguistic Landscapes of certain neighbourhoods of Istanbul, in particular the Kumkapı neighbourhood in the district Fatih. Our conversations resulted in the question whether the outcome of Linguistic Landscape research is comparable when done by different researchers – just in line with the axiom in empirical science that research should be reproducible. We designed a test field whereby two researchers collect Linguistic Landscape data of the same stretch of road and consequently compare the datasets (and, in a later step, the results). This blog post reports on the experiences of the first step, i.e., the process of data collection.

In the following, we briefly describe the methodology of data collection before sketching our experiences and problems that emerged in the process.

Methodology: What, where, how?

For our experiment, we selected a stretch of road of approx. 220 m length (221,54 m on Google Maps) in the Kumkapı neighbourhood of Istanbul’s Fatih district (Tr. ilçe). This amounts for both sides of the street, thus for a stretch of 440 m of landscape. The area was familiar to both of us from earlier research we had conducted there individually in previous years (see Schreiber 2017; Bartholomä, Schroeder & Yapar 2022). Kumkapı is particularly interesting for Linguistic Landscape research due to its history as a Greek and Armenian fishing village, continuing as a residential area in the second half of the 20th century hosting not only non-Muslim minority groups but also internal migrants from Eastern Anatolia. Due to its proximity to both the touristic area of Sultanahmet and the commercial areas of Laleli and Beyazıt, Kumkapı has seen a considerable influx of groups from Ex-Soviet countries, as well as from Arabic and African refugees. We concentrated on the neighbourhood (Tr. mahalle) of Muhsine Hatun and in particular on Tavasıçeşme Sokağı, a primarily residential street with some shops and smaller businesses located between Türkeli Caddesi/Çifte Gelinler Caddesi and Alişan Sokağı at the heart of the neighbourhood (see Fig. 4). Each of the researchers collected data there individually: Ruth Bartholomä (henceforth RB) on Saturday, 18 February 2023, in the afternoon (between 16:04 and 16:19, i.e., over a period of 15 min) and Laurentia Schreiber (henceforth LS) on Tuesday, 21 February 2023, around noon (between 13:27 and 13:54, i.e., with a duration of 27 min). The difference in the time span both researchers required for the same task of data collection was a first interesting observation we made. Furthermore, while LS entered the street from the south and documented the right side first before turning around, RB started her documentation of the right side coming from the north.

A familiar problem in Linguistic Landscape research is the choice of objects of documentation. We define a ‘linguistic sign’ as “any written manifestation of human language in the public sphere” (Ben-Rafael et al. 2006: 7), which includes graffiti and pencil writings but ignores mobile objects like text on cars or clothing of passers-by.

Results: What we learn about the collection of Linguistic Landscape data

The corpus of RB contained 85 photos from Tavasıçeşme Sokağı, while LS collected 82 photos, whereby not all photos featured the same signs. This is despite of the fact that both researchers tried to follow a ‘one sign – one photo’ policy, which was, however, not always possible, for example, when physical obstacles occurred in the way.

In the following, we report on several issues we encountered in the process of data collection:

- definition of a ‘linguistic sign’, i.e., ‘Do we collect the same signs?’,

- general obstacles in the process of data collection,

- technical issues,

- differences in perception, i.e., ‘Do we see the same things?’,

- ethical considerations such as ‘Does the researcher affect the ‘object’ of research?’.

(i) Issues in the definition of a ‘linguistic sign’

Despite our clear definition of a ‘linguistic sign’ (see above), questions arose regarding which kind of signs should be documented. For example, it is questionable whether numbers indicating years or prices (Fig. 5) are relevant.

Other ‘critical issues’ are names of buildings (Fig. 6) or omnipresent brand names such as ‘Coca Cola’ (Fig. 7), ‘Adidas’, ‘Vodafone’ and the like.

Another question concerned whether to include unobtrusive emblematic signs such as:

- sticker and badges, for example from the tourism industry such as Trip Advisor, Booking.com or prompts such as “Review us” (Fig. 8);

- graffiti and permanent marker drawings (Fig. 9; see Gaiser & Matras’ 2016 ‘emblematic’ category of signs);

- emblems such as “Türk Telekom” (Fig. 10), “danger of death” (Fig. 11) or municipality names on garbage containers (Fig. 12).

A further issue was the documentation of broken, torn or other vanished signage (Fig. 13 and Fig. 14) and whether the researcher may and/or should make efforts to document these, e.g., to fold back loosened signs to take a photo (Fig. 15).

Some critical issues also concerned the recurrence of signs:

- Should signs with the same content that appear at different points along the street be documented each time (Fig. 16a and 16b)?

- Should shop signs of large and frequent companies, such as supermarket chains or mobile communication companies, be documented every time they occur or only at the first appearance?

- Should several related signs on the same object be counted as one or be documented separately, for example, shop names indicated at different places at the front of a shop (Fig. 17–19)?

Regarding the recurrence of signs, we are inclined to follow Kallen (2023: 154–155) in documenting ALL signs however frequent they occur and counting each unit separately, as frequency can be considered a means to create dominance and effect. For the other questions, the solution will depend on the choice of the researcher guided by specific research interests. However, for projects in which data is collected by several people, it is important to define binding rules in advance.

(ii) General obstacles

The following general obstacles occurred in the process of data collection: closed shutters, parking cars, drying racks and other obstacles on the street, as well as (groups of) people which all led to the fact that either no photographical documentation was possible or that the pictures had to be taken from afar of from an angular perspective. The following example shows the consequences: While RB was able to document the signs in the shop window of a cargo company, which included a sign in Armenian (see Fig. 20), LS only found a closed shutter (see on the right side of Fig. 21) when she documented the Linguistic Landscape a few days later.

The corresponding sign was therefore not part of LS’s data corpus what we discovered when we compared the languages that occurred in our corpora.

(iii) Technical issues

Technical issues were experienced in the quality and speed of the camera. All photos were taken with mobile phone cameras as a convenient way to get the photos with corresponding GPS coordinates. A general obstacle formed LCD-displays with changing screens which were barely visible on the photos, depending upon the quality of the camera (Fig. 22).

Another factor was the quality of the photography which in part depends on the skills and individual style of the researcher, but also weather conditions and lighting play a role. Finally, technical problems such as errors in data storage and data loss should be avoided at all cost, by using quality cameras, if possible – and by sustainable data management.

(iv) Differences in perception

We noticed differences in the individual perception of researchers, for example in noticing signs high up on house fronts (Fig. 23 and Fig. 24) or nearly hidden signs.

This left us with the question up to which height signs should be included. Furthermore, we wondered whether the perception of signs differs with the observant and whether a resident of the neighbourhood perceives the signs in the same way as a visitor to a neighbourhood.

(v) Ethical considerations

Some ethical considerations are in order regarding the role of the researcher in the landscape and whether the researcher becomes an agent via their sheer presence. This includes for example conversations with residents, who might perceive the process of documentation as intrusive and inquire about the purpose of the photo documentation. We assume that the presence of the researcher inevitably has an effect on the landscape, which is co-created by all agents in an ephemeral way, and that therefore research should be conducted in a responsible manner. This could entail, for example, that the researcher is willing to engage in conversations and respond to questions of passers-by, but also that the researcher stays in the area for some time, not only for ‘observation’ but to ‘give something back’ – be it not least via supporting local economy. The ethnographic approach to fieldwork is (at least in part) able to account for this (Blommaert & Jie 2020; see also, e.g., Rice 2012 for ethical issues in linguistic fieldwork, and references therein). In any case, the researcher should be aware of their impact and should reflect about their behaviour in the ‘field’ to be able to act as responsible as possible in a given situation.

Summary & what is next

In our experiment, aiming to test the influence of the individual researcher on the research process, we experienced clear differences already in the first step, i.e., the process of data collection, despite the same research aim and well-defined methodology. It remains at this stage open, though, whether the differences in the sampling process also led to different outcomes of the study. In the next step, the results of the study should be compared. Data analysis is likely to yield new critical issues such as the identification of languages on the signs which is to a certain degree determined by the language competences of the researcher (as in the case of the Armenian sign mentioned above, which both of us were not able to decipher) or differences in a quantitative versus qualitative approach to data analysis. As for data collection, we conclude that reproducibility and objectivity of a Linguistic Landscape study are not immanent and require very clear and detailed agreement on the relevant definitions, although ultimately, the ‘human factor’ cannot be neglected.

References

Bartholomä, Ruth, Christoph Schroeder & Diren Yapar. 2022. “Spiegel sprachlicher Vielfalt: Datensammlung zur Linguistic Landscape in Istanbul”. Orient-Institut Istanbul: Newsletter Frühjahr 2022, 29.

Available online: https://oiist.org/publikationen/newsletter/ (last retrieved 19 July 2024).

Ben-Rafael, Eliezer, Elana Shohamy, Muhammad Hasan Amara & Nira Trumper-Hecht. 2006. “Linguistic Landscape as Symbolic Construction of the Public Space: The Case of Israel”. International Journal of Multilingualism 3(1), 7–30.

Blommaert, Jan & Dong Jie. 2020. Ethnographic Fieldwork: A Beginner’s Guide. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Gaiser, Leonie & Yaron Matras. 2016. The Spatial Construction of Civic Identities: A Study of Manchester’s Linguistic Landscapes. Manchester: University of Manchester.

Kallen, Jeffrey L. 2023. Linguistic Landscapes: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Landry, Rodrigue & Richard Y. Bourhis. 1997. “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality. An Empirical Study”. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16(1), 23–49.

Rice, Keren. 2011. “Ethical Issues in Linguistic Fieldwork”. In Nicholas Thieberger (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Fieldwork. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 406–429.

Schreiber, Laurentia. 2017. “Visualising the Invisible: Linguistic Landscapes of Kumkapi Neighbourhood in Istanbul”. Paper presented at the 33. Deutscher Orientalistentag, Jena (Germany), 18–22 September 2017.